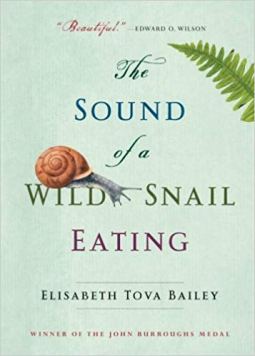

This is one of the most enchanting books I have read; a gentle, contemplative book that chronicles Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s year-long relationship with a snail.

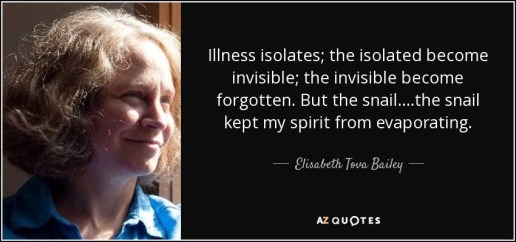

In her 30s, Bailey contracts a debilitating neurological disorder that leaves her bedridden, barely able to sit up, let alone stand. She has to move from her farm house into a studio flat to be closer to help, leaving her dog and her outdoor lifestyle behind. Confined to bed, she experiences a loneliness that chronic illness can bring, when friends are unsure how to be around you, and she starts slipping into a dark place in her mind, experiencing panic attacks and great despondency.

One day a friend brings her a potted field violet on which she has purposefully put a woodland snail for Bailey. She is left bemused, wondering what on earth she is to do with it. Why should she enjoy a snail? How could she look after it when she couldn’t look after herself? She couldn’t even return it to the woods.

When the snail starts to crawl out of the pot that evening, Bailey thinks she won’t see it again and falls asleep, but when she wakes, she sees it has returned to the same place and that the envelope nearby has a few small squares chewed out of it. Thinking somewhat guiltily that the snail can’t live on paper alone, she puts a few flower petals near it and later, in the silence that fills the room, she hears the snail chewing on them.

“The sound was of someone very small munching celery continuously … the tiny intimate sound of the snail’s eating gave me a distinct feeling of companionship and shared space.”

And so the relationship between Bailey and the snail begins. With a new companion, as unlikely as it is, Bailey refocuses her attention from herself to the snail and in this way, her illness becomes more bearable and less lonely. As the snail is nocturnal and Bailey an insomniac, she spends hours observing its behaviour, and the tenderness and skill with which she writes about the snail makes this unusual subject a joy to read about.

“Each evening the snail awoke and with astonishing poise moved gracefully to the rim of the pot and peered over, surveying the strange country that lay ahead. Pondering its circumstance with a regal air, as if from the turret of a castle, it waved its tentacles first this way and then that, as though responding to a distant melody.”

Concerned about the snail’s living space, she buys a terrarium and recreates a woodland world for it to live in; she finds out what sort of food snails eat and feeds it mushrooms and egg shells. She starts reading widely about molluscs to learn more about her unexpected roommate, and the more she discovers about the common snail, the more respect she gains for it. She trawls gastropod literature, from Darwin to poetry to modern-day scientific research, making this as much a natural history or educational book as it is a memoir.

“A snail has an interesting life; its courtship is remarkable, its various natural abilities are astounding, it has a memory, and, just like humans, it likes a comfortable place to sleep and very good food.”

It is a relationship of observation; Bailey doesn’t anthropomorphise the snail – she contemplates giving it a name, but in the end decides ‘snail’ is the best moniker. She doesn’t touch or stroke the snail or make demands of it; she watches it and learns. In this way, I also learned. Who knew that most snails are hermaphrodites, and that snails have a mating courtship? Who knew that after fertilisation, they can hold off having babies for months? Bailey didn’t – until her snail unexpectedly lays eggs and her room turns into a snail crèche, hosting 118 baby snails at once stage.

Having had a chronic fatigue illness similar to, though not as severe as, Bailey’s, and being able to relate to the profound loneliness of an often-misunderstood condition, I found her experience almost unbearably touching, and admired her ability not to slide into self-pity at any stage, and to stay in the beauty of the moment.

This is a short book, but a physically beautiful one with small line drawings of snails trawling through its pages. Its quiet meditative tone makes it a soothing read, and left me feeling that something good still exists in the world when humans and nature can connect in this tender, trusting way.

Visit Elisabeth Tova Bailey’s website at http://www.elisabethtovabailey.net